If there is such a “thing” that could be labeled as the Holy Grail of surfing, it would surely be the surfboard itself. At least I think so. The surfboard is the mechanism used by surfers to ride the waves, but I’m sure you are thinking to yourself-”DUH. You must think we are all stupid. What’s your point?”

My point is… without the surfboard, surfing would not be the multi-billion dollar industry that it is today. Yes, that’s right, I said billions. Sure, you could body surf, but a surfer’s worst nightmare is finding themselves somewhere at the far fringes of civilization, staring at an empty lineup of perfectly groomed, never before ridden waves… and no surfboard. I would cry like 6 lb. 4 oz Baby Jesus probably did upon delivery. The surfboard started everything. We need the surfboard. The surfboard IS the Holy Grail of surfing. End of story.

Hopefully I have made my point and you will agree that the surfboard was a pretty damn cool invention, with the surfboard fin being the second coolest. Of course the history of the first surfboard is as vague and argued about as the origins of surfing itself, so I won’t proclaim to be a historian about those topics and leave such discussions to the likes of Pohaku Stone, Matt Warshaw, Nat Young and a hand full of others who have spent years researching both the history of surfing and the surfboard.

My story has to do with a more mundane and tragic aspect of the surfboard. This particular aspect has a vague and mysterious history too and I have been researching it for years. In fact, just a few days ago, I had the opportunity to chat with some of the top leaders in the surfboard industry about this exact subject, while attending Surf Expo in Orlando, Florida. It’s a tough, touchy subject that takes diplomacy and big cojones to even bring it up. Since I was born with a pair, here goes:

It has to do with the perceived value of a product and in this case, a surfboard. After 30 + years of studying it, while being on the front lines of the surf industry as a surf shop owner and as a board builder, I continue to struggle with this variable and constantly ponder it.

The bigwigs at the trade show didn’t seem to know much more than me. It is perplexing, to say the least.

First, a price baseline was established early on and it worked well for a time. Several years later, a certain someone drew a line in the sand and proclaimed a new mandate and, OH BOY, as to why that person did what he did back then still continues to be an enigma. I’ll refer to the conspirator as Cassius Longinus.

Evidently, the surfboard meant nothing to him. My guess is that he also harbored ill will towards artists. Being that making surfboards is an art and art is subjective… well, his baseline reflected his disdain for the art of making surfboards. Somehow, his baseline has continued to withstand the test of time. Please humor me long enough to give you a crash course in Fulbright Surfboard Economics 101.

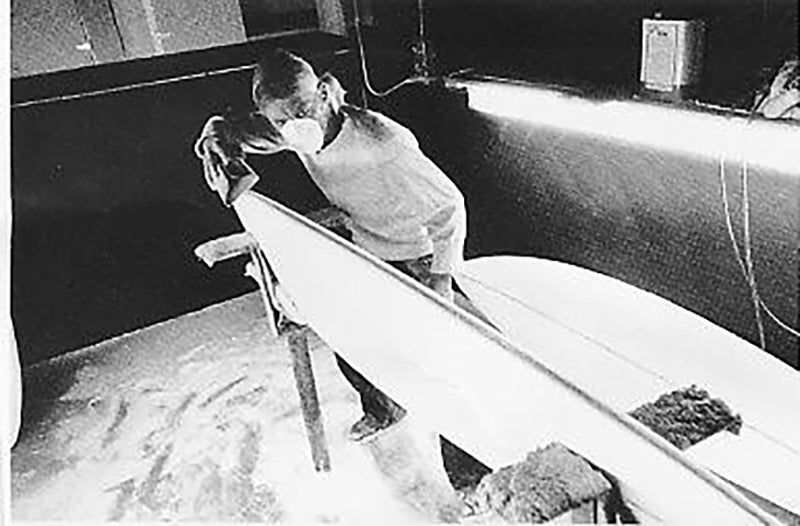

Building surfboards for profit started out as a genuine cottage industry. The first ones were most often made outside the homes of surfers or inside their garages, pending parental approval.

Surfing was indeed still a niche hobby and production usually occurred when the surf was flat. It was a simple, magical time. A time before respirators and removable fins. A time when you could build a surfboard in your garage for $45 and sell it to your neighbor for $90.

It was a simple time where you actually hoped you could find another surfer to go out surfing with you. Surfing was a small band of rebellious youth who just wanted to ride waves, hang out at the beach by a bonfire at night and impress the beautiful girls who were intrigued by them.

Then Hollywood found out about their goings on and launched a string of beach movies about the surf culture. Gidget paddled out and the rest, as they say, is history. In fact, it was the true birth of surf commercialism. The demand for surfboards increased a thousand fold, as did the crowds. Somewhere on the crowded beach, probably dressed in an all black suit with dark sunglasses and possibly wearing loafers with the slotted pennies, stood young Cassius…lurking.

In 1961, surfboards still sold for about $120, give or take. The volume of surfboards made during that era was staggering too. Factories like Velzy’s and Bing’s were producing hundreds of surfboards a week! The who’s who list of shapers who responded to the demand were supermen, whose daily workload still boggles the mind.

Despite their valiant efforts to step up to meet the behemoth demand, they still couldn’t keep up! The industry’s first, molded “pop-out’s” were then introduced into the marketplace. They were crude looking shapes, many times sporting famous names, like Duke Kahanamoku, that were mass produced and popped out of a mold, hence the name pop-out.

It is important to note that prior to the first launch of molded surfboards, all of those thousands upon thousands of surfboards made by the manufacturers of the day were made start to finish by hand. Making a surfboard was and continues to be a very labor-intensive process. The pop-outs of the early to mid 60’s were an inexpensive option for beginners or the unwary. Both types however still had a solid perceived value. Hence a respectable profit margin.

Markups remained in the 40-50% range, which seemed to be the norm for other “sporting goods”. Considering that all the first surf shops of that period were owned and operated by the actual surfboard makers themselves (Velzy being the first), there was no middle man. Shape them out back and sell them in the “showroom” up front. All profits went straight back to the shaper.

The pop-outs of the time were usually sold in hardware stores, sporting goods stores, and other random inland establishments. Even though they were less expensive to produce than a hand-made surfboard, by using lower quality materials and a molded process that reduced labor, it allowed the maker to produce and sell them to a retailer for less than the cost of a premium hand shape, while keeping the profit margin for their retailers in line with the surf shops.

Regardless of the makeup, surfboards were a profitable commodity. During that period in surf industry history, the number one driving force of the industry was the surfboard! Other than surfboards, the surf shops only carried t-shirts sporting their own board logo (retailing for $2.00) and their decals. A surf shop’s entire success depended on and actually thrived on surfboard sales. Think about that for a second because it didn’t last long. Somewhere, still lurking in the shadows…Sir Capitalist Cassius schemed.

Fast forward a year or two. Basically overnight, the industry hit puberty. On one day you had a happy go lucky surfer, riding a big ol’ stable platform, casually walking the nose on their 9’6” Weber Performer. The next day they were deeply concentrating on a seagull flying above a breaking wave while tripping out of their mind on LSD. Then eight hours later they noticed they really did cut two foot off the nose of their surfboard!

The next chapter of the surfboard industry arrived in the form of innovation, experimentation and the death of the longboard. It shocked the status quo. There came a disturbance in the force that not only wiped out many of the original Godfathers of the surfboard industry but also created somewhat of a governor, in terms of crowd control, at least for a time.

The longboard had been a stable, fun, family friendly and basically an auto pilot cruise mode machine. The new, much shorter and more radical surfboards that were introduced were lighter and more maneuverable but much more challenging to ride. The surf masses went from riding something akin to an old, put out to pasture kids horse to bareback riding a wild stallion.

The time had come to separate the wheat from the chaff…cull the herd…many just couldn’t make the transition, including board makers. Pre-existing surfboard factories were still filled with (then) obsolete longboard foam blanks and obsolete finished product in their showrooms that they literally couldn’t give away. They either couldn’t recover financially or wouldn’t adapt and shuttered their operations.

There was a new kid in town and he changed the game. New blank molds and variable foam densities were created, experimental designs were perfected through trial and error, fins were modified and removable and fiberglass materials had to be updated. Screw durability. Now, light was right! It was all about progression, performance and who pushed the envelope in technology and design. All that progress came with a price tag.

Surfboard designs were in a constant state of flux, more so than ever. So many ideas and so many talented shapers and surfers propelled surfboards to a new level of high performance. It was a brave new world but a world with fewer people wanting a surfboard.

The Gidget craze crowd had already retreated back to Pasadena. The new surf shops that sprouted up to sell these new UFO looking surfboards responded to a now seemingly lackluster demand for boards by not only selling t-shirts, like the original surf shops had done, but they also added more recent surf industry inventions like the wetsuit and the leash to their inventory. Some even incorporated health food cafes, head shops or other surf hippy attractions into the mix to complement their surf shop identity and supplement their surfboard sales. They had to wear a lot of hats just to keep the doors open.

Obviously, the days of surf shops banking on surfboard sales to support them were over. It didn’t help matters that the country was in the middle of a deep recession. Surfboard sales were down and manufacturing costs were up, as the OPEC oil embargo of ‘73 nearly quadrupled the price of the petroleum-based materials used in surfboard construction.

Board builders were forced to compromise their profit margins. That was a pivotal moment in surfboard history that unfortunately further reduced not only the perceived value of a surfboard but also reduced the profits for the futuristic thinkers/shapers responsible for reinventing the wheel…surfboard in this case. They all deserved so much more money than they were getting, but the recession, coupled with a floundering surf industry forced them to low-ball themselves just to get by.

I imagine the decision to charge more for their work was too risky, given the state of the economy. The recession had tightened everyone’s belt, especially surfers, given their tendency to surf more and work less:) The time was right, though. The boards that were produced really were better as was the talent pool. That should have translated to increased perceived value.

That period was the most exciting time for innovation, designs, artistic expression and the quality of production but the worst time for profits for surfboard designers. During the early to mid 70’s, some of the most talented shapers to ever represent the board industry propelled surfboard hull designs, rails, rockers, foils and fins to new heights that we are still trying to decode to this day. Some of those forward-thinking board makers and surfers were Mike Hynson, Herbie Fletcher, Mike Diffenderfer and Dick Brewer just to name a few.

Core surfers were dancing in the streets, celebrating a temporary moment of disinterest from the masses and riding finely tuned equipment that took them to new heights. The new board designs allowed surfers to invent new maneuvers, ride inside the tube (and come out) and boldly surf where no man had surfed before. They certainly were much easier to travel with than a 40 lb. 9’6″.

The hardcore surfers of that time were optimistic that they could go back to “business as usual” of being left to their own devices, empty surf breaks, feral travel adventures and of course debauchery.

The surfboard industry, on the other hand, needed something more than the meager profits associated with the current surfboard pricing structure. To them, surfing was their livelihood and put food in their babies’ mouths. Was now the time to try and raise their prices to better reflect their efforts or…..? Well, another solution would present itself. The surf industry would finally get a seat at the big boy table. You may have noticed I didn’t say the surfboard industry…they sat at the fold-out card table with the kids.

The industry would graduate from high school and go to college. Their major? Fashion. Yeah, for real. The surf industry would enter a new chapter in growth and profitability and once again make surfing cool to the masses.

For surf shops, it would give them a badly needed shot in the arm, profit margin wise, but it only further devalued the one product that started it all. That was the moment in history when the surfboard, the one ingredient that truly meant anything to a surfer, basically became the industry’s loss leader (a product with little to no markup used to draw more people into your store, hoping they would buy other items with a high markup).

Using the surfboard as a loss leader is as low as you can go. Surfboards were trumped by fashion because that was where the real money was. For a surf shop owner, surfboards had a low-profit margin in comparison and tied up a significant amount of money. Fashion, however, had a very hefty profit margin. They had a bingo! “Keystone” is a retail word that describes any item with a 100% markup. The “surf fashion” industry entered the market with a keystone suggested retail price across the board.

Surf shops of that period had already dabbled a little in boardshort sales, mixed with their surfboard inventory, t-shirts, wetsuits and leashes but “surf baggies”, as they were then called, were still just considered a hard good item to the surfer, not a fashion piece to the masses…just yet.

Distribution was limited and controlled, through an authorized dealer approach. If Joe and John both had surf shops in Leucadia, John would sell Katin and Joe would sell Birdwell Beach Britches. The same concept applied to surfboard labels, as John would be an authorized dealer for Plastic Fantastic and Joe would be the local Gordon & Smith dealer. They were two surf shops competing against each other in the same community but their offering was unique to their store. It’s called healthy competition. A brilliant foundation had been poured there. More surf shops were opening, more surfboard brands were coming into the fray, more wetsuit companies entered the industry and the time was ripe to deliver that billion dollar baby- mainstream surf fashion!

The advent of surf fashion suddenly became the driving force that helped propel surfing further toward the multi-billion dollar industry of today. For surf retailers, surfboards became more of a liability than an asset.

Surf fashion took the sport from a recreational pastime with limited profitability to where it is now so I must give credit where credit is due, beginning with brands like Katin and Birdwell Beach Britches, followed up by Hang Ten, Op and Sundek.

Then, the industry really got its sea legs with giants Quiksilver and Billabong. Then, along came the more niche brands. The favorites were Stussy, Shroff, Mossimo and Bessell. Of course, numerous more have come and gone since…so many.

The surfboard that once fueled the entire industry for two decades became nothing more than a prop. Now, surf shops were doubling their money on all the fashion trappings like bikinis, sandals, boardshorts, hats, t-shirts and what’s called “cut & sew”. The surf industry rag merchants designed pants, button-up dress shirts, jackets, fleece, flannel…you name it.

As a shop owner, why would you not put all your money into products that have the highest demand and the highest profit margins? Why not just hang 3 (or maybe push the envelope to 4) surfboards from the ceiling (as to not take up precious floor space) and sell the shit out of the surf fashion craze? That was exactly what happened and right about the time I decided to enter the surf industry. I followed my own path but that’s another story. We are talking about the early 80’s here.

Remember the early 60’s example I mentioned about the local shaping guru who spent $45 to hand build a surfboard and turned around and sold it to his neighbor for $90? That was a keystone sale. The perceived value of the surfboard by the shaping guru and the surf enthusiast neighbor was in perfect harmony.

Even after that now infamous early 70’s OPEC oil embargo and subsequent cost increase in petroleum-based products and even though surfboard prices rose, you could still retail a surfboard for a price that had close to a 40% profit margin. Yes, the recession and materials cost had pushed the price up but the perceived value of the surfboard, although down, could still net a reasonable yield.

The manufacturer wholesaled the retailer his newest 6’11” Summer Fish for $275 and the suggested retail was $399. There’s your 40% margin. By the time the 80’s came around, board prices went up and the profit margin had shrunk to roughly 30%. While prices went up, profit margins for surfboards continued to fall. Luckily, for some shapers, a new surfboard market had opened up, where demand was high and perceived value was even higher…Japan.

They had been paying close attention to the U.S. surfboard scene and invited many upper echelon shapers to come overseas and make surfboards. They got it. They treated shapers like VIPs and they were paid handsomely, compared to in the U.S., where they were getting paid about $35 to hand shape a surfboard.

In fact, in the U.S. the production shapers of that time were losing their jobs. Some of the first shaping machines were coming on-line. Now, they were competing against and being replaced by “the Terminator”. The surfboard, the most coveted item a surfer possessed, had once again fallen victim to a lower perceived value.

Many shapers started brushing up on their ding repair skills! It didn’t help matters when the retail ceiling space became the surfboard’s new home. In the early 80’s, the surf shops in my community had a surfboard inventory of between 3-10 surfboards. If you wanted to further inspect one or, God forbid, buy one (that would compromise their motif), they had to get a ladder and pull it from the ceiling. Hell no-they didn’t have time for that nonsense. They were too busy making a small fortune from the cool surf fashion craze.

To them, the 30% profit margin on their perfectly good decoration was preposterous. I agreed with their dislike of the profit margin but didn’t agree with the fate of the surfboard. It would get even worse-tragic in fact. If it had happened in the 50’s, everyone would have screamed, “communist plot”!

Some dip-shit plotted a grand plan to put a ceiling on the retail markup of the surfboard. I am sorry for the pun but not really. The dip-shit I refer to as Cassius Longinus. It was beyond my comprehension because, at the time, surfing was in a renaissance period, in part due to the hugely successful surf fashion industry becoming mainstream. There was also a thriving amateur and professional surfing circuit getting the attention of the mainstream media. The best part of the renaissance?? The surfboards!

The surfboard designs of the period (1980-’85) were off the hook. To this day, I still believe the early to mid 80’s was the best time for surfboard design. The 12 x 20 x 15 x 2 1/2 flat deck, low rocker, boxy railed, squash tail, tri fin surfboards of that time were game changers! Those surfboards were fun, user-friendly, oftentimes colorful and they worked insane! We had good local shapers and bought surfboards from the likes of Tim Bessell, Shawn Stussy, Gary Linden, Lance Collins…Jesus the list goes on and on. That was a magical time for surfboard design and would have been another perfect opportunity to correct a surfboards’ perceived value but noooooooo.

An executive order was written and rumors spread through the ranks. Cassius stood at his podium and proclaimed, “ The retail markup of the surfboard shall be…..drum roll……. (he pulls a brown, super old looking, rolled up parchment from his ass) and said $100”.

Legend has it that after he spoke those treacherous words, as he attempted to roll up the parchment and stick it back up his stupid ass, someone in the tradeshow crowd noticed his concealed dagger, the very one that his Great-Great-Great-Great-Great-Great-Great-Great-Great Grandfather he was named after used to stab Julius Caesar! The trade show crowd froze in fear. I guess nobody wanted to get shanked by a distant relative of one of Caesar’s vicious, scheming murderers. That is virtually the only reason I can come up with, as to why that standard was accepted without question.

Everyone just followed along, in a straight line, and marched into a very dark space we are still not able to feel our way out of because apparently, the perimeter is protected by The Great Wall of Complacency. It keeps us surfboard makers quiet and in line…appreciative of any crumbs we may get thrown.

As surfboard builders and surf retailers, a surfboard’s worth and profitability were now penned on parchment and predetermined for all. Here-Here. Without a rebellion of epic proportions or an extension ladder, we will remain within the confines of the walled up shit-hole we are in. If anyone tries to buck the system, they will first be forced to endure the online walk of atonement. You know, the surf forums–a public, yet anonymous slander-land where “sir-surfalot” tears you a new one and destroys your character at the swipe of his mouse and stroke of his keyboard. Then, and only then, will you be banished forever from the City of Surf.

It is truly a tragedy that the art of hand making surfboards is so undervalued, under appreciated and all but obsolete. It is also tragic that many surf shops continue to use the surfboard as a loss leader. I suggest you change your wicked ways and put the surfboard back on the pedestal, where it belongs. Over the past 60 years, the perceived value of the surfboard has continued to decline. So much, in fact, we have delegated the future of surfboards to the factories in Asia, all of whom have the latest version of the Shape 3D CAD program… better margins too.

Every time I’ve heard anyone in the surfboard industry talk about their trade, they always described it as a labor of love. That’s sad but describes it perfectly. That’s code for, “I’m not making any money”. Everyone always warned me that there was no money in surfboards, but I continued to pursue it anyway because I can’t help myself. I’m weak. I love it. The legendary men who first started making surfboards as a trade are my heroes. To everyone who continues to try to eek a living out of making surfboards, I salute you. I ask only two things of you. Go up on your prices and bring me the head of Cassius Longinus 🙂